Much like his predecessors and peers, M.F. Husain was drawn to the subject of India’s colonial past. He started working on a series of Raj theme paintings that embody his take on this period of Indian history by the 1980s. Dubbed originally as the ‘Images of the Raj’ when the artist first started producing them, their themes and motifs would subsequently spill over to Husain’s succeeding series until the later part of his life. But compared to other artist’s serious treatment of the subject, Husain’s Raj bordered on the satirical, combining elements of history and witty commentary on the effects of Raj on society and oftentimes juxtaposing contrasting subjects in the painting to illustrated the opposing dynamics present, ‘each subtly absorbing the identity of the other and each equally subtly resisting that absorption.’ (D. Herwitz, Husain, 1988, p. 19.)

Arguably one of Husain’s more popular series, the period of British colonial rule or most commonly referred to as the Raj, resulted in some of the sharpest, perceptive, and also most spirited, of works that he produced throughout his prolific career. “These works are densely packed with objects and people (British and native, high and low, male and female) and some animals as well, brought together in narrative action enormously revealing of the anxieties of imperial rule in India, even as their absurdities elicit a chuckle or smile from the viewer.” (Sumathi Ramaswamy, Husain’s Raj, The Marg Foundation, June 2016, pg. 12)

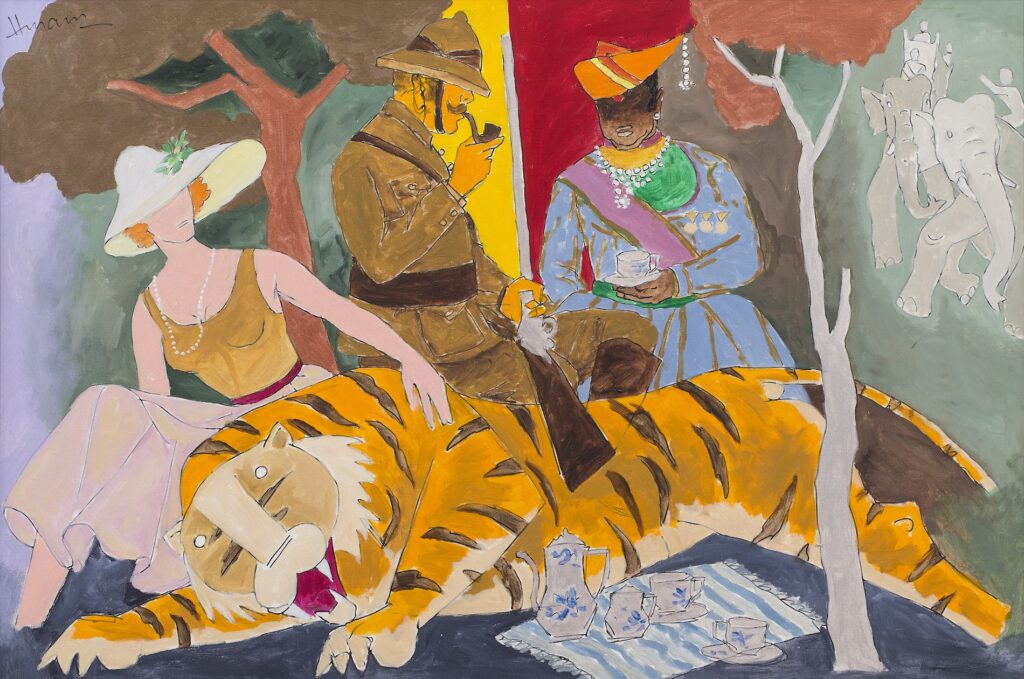

Titled ‘Afternoon Tea after the Kill,’ Husain depicts two of the most British tradition during the era, tea time and tiger hunting. With the sport referred to as ‘colonial hunt.’ The picture alludes to the defeat of the tiger, the conquest of India, and the eventual lengthy crown rule that follows. But aside from the obvious interpretation, the fallen animal was depicted resembling ‘Tipu’s Tiger,’ a mechanical tiger savaging a British soldier commissioned for Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore, and one of the fiercest and implacable enemies of the British. He was, however, defeated and killed in 1799. While the ‘colonial hunt’ represented domination of nature and natives, it also became the point of contention within the elite due to the perceived connection between hunting, power, and privilege, as hunting came to be regulated by laws by the 1900s.

Like his other paintings, his figures are intentionally obscure with vague references to historical figures that are often intentionally fictionalized. Here, the featureless Western lady wears a sleeveless dress with a sunhat, her companion is draped in his hunting garb while his counterpart is dressed in the majestic garb of a Maharaja. The tiger is placed most prominently in the center, reminiscent of photographs of British royalty photographed aside dead tiger carcasses from the same period. The Shikars, the traditional Indian hunters turned guide, is seen atop the elephant almost blending with the background.

Husain’s recall of the Raj is intensely personal but also fiercely political, a painter for the people, he immortalized each period of Indian history in his canvases, celebrating and informing his audience of the amalgamation of periods that gave rise to the composite culture of the present. By choosing to cast his eyes back to this particular period, he produced powerful works charge with nationalism and humor that are global in its form yet deeply Indian in its content.

Auction Catalogue – South Asian Art – ‘Modern and Contemporary’ – September 24 – 28, 2020