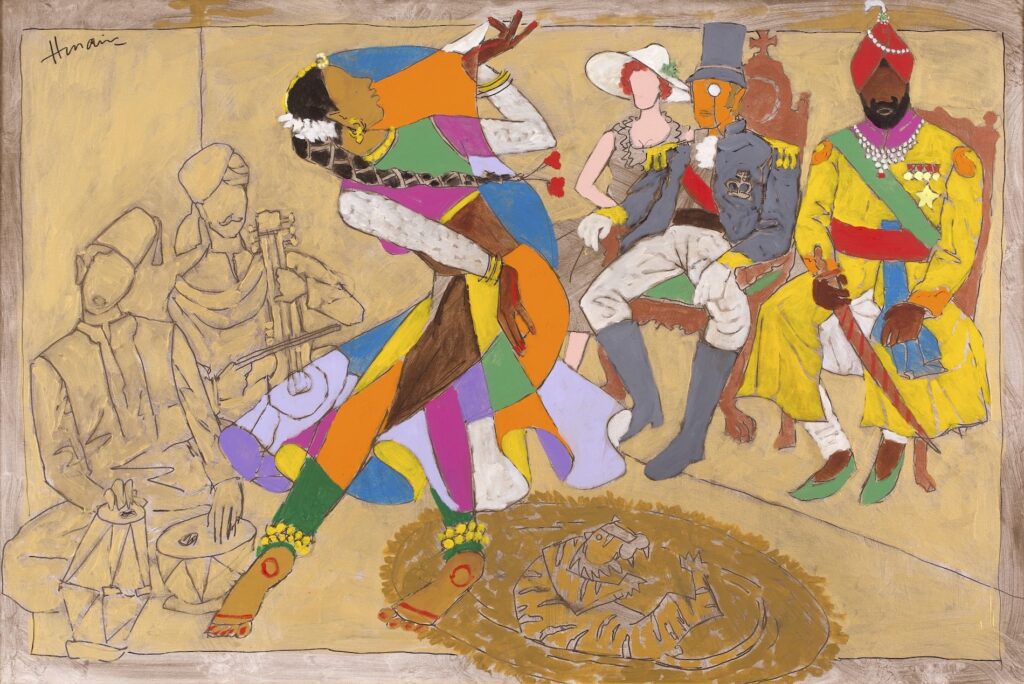

Leading ARTIANA’s upcoming South Asian sale is this exquisite work from M.F. Husain‘s Raj Series – ‘Kathak Dance Performance at the Maharaja Darbar’ painted in 1989 with impeccable provenance.

“In the mid-1980s, at the height of his celebrity as India’s most famous and flamboyant modernist and living artist, Maqbool Fida Husain cast his painterly eye back half a century and more, to a time when much of the subcontinent was still under British rule. This sharp – and surprising – (re)turn to India’s recent colonial past resulted in some among the most insightful, and also most playful, of works in different media to emerge from the brush of this prolific and imaginative artist.”1

With regards to his treatment of the British Raj subject, Husain simultaneously mimics two separate styles of British-Indian painting: formal portraiture using prominent imperial emblems and icons, and picturesque that exaggerated exotic elements.2 Husain satirized the confluence of cultures yet he does not historize his subjects; references to historical figures are intentionally oblique and were often fictionalized.

In a large scale tableau, the Maharaja’s darbar is complexly marked with Husain’s iconography —the dancer and the musicians with their traditional instruments. The titular Maharaja holds court and sits comfortably on his home ground. Sitting beside him is the English governor who is stiffly dressed in a formal military suit, decorated and bearing the symbol of the crown; with him is his Lady seated a little to the back. Historically, a darbar refers to a ruler’s court and later to ceremonial gatherings characterized by pomp and glamor during the British colonial era. It signifies the ruling Maharaja’s demonstrations of loyalty to the crown. Instead of a dismissive attitude towards this practice of paying homage to the colonizer, Husain presented both English Lord and Maharaja side by side, in equal prominence. “His India has much authority and it forms a rather bemused backdrop for the historic mutual incomprehension that the Raj embodied, He situates his presentation of the drama of the colonizer and the colonized within a discourse of equivalence.”3 Interestingly, the tiger motif that is reminiscent of Tipu’s tiger is present.

Aside from the principal subjects, the entire composition is almost devoid of colors. The kathak performer is the most colorful and dominating feature, highlighting Husain’s choice to portray India’s long artistic tradition as a continuum. Dance, particularly Indian classical dance, was heavily censored during the colonial period. The accumulation of Indian classical dancers into his pictorial tradition juxtaposed with the subject of the British Raj marked Husain’s interest in merging dance, visual art, and history by turning back to earlier indigenous forms of presenting the female body.

Husain’s work on the British Raj “provides both the political and ethical charge that runs through his works and it also distinguishes Husain’s attempts to laugh at the empire from other artistic attempts to do so that had preceded him. He really is the only major artist of his generation to deliver this message (offering) a playful but nonetheless edgy postcolonial lesson in how one might hate and disavow empire in the right way, even while learning how to live with it, mock it and laugh at it properly.”4

Text References:

1 S. Ramaswamy, Husain’s Raj, Visions of Empire and Nation, Mumbai, 2016, p. 12

2 S. Bagchee, “Augmented Nationalism: The Nomadic Eye of Painter M.F. Husain”, Asianart Online, 1998, accessed April 2019

3 Ibid.

4 S. Ramaswamy, Op. cit., p. 133,139

Auction Catalogue – South Asian Art – Modern and Contemporary – June 13-17, 2019